Prenatal Care Coverage Increases Treatment for Gestational Diabetes

Medicaid covers both prenatal and postpartum care for many people in the United States who have low incomes, but current federal law allows Medicaid coverage only for U.S. citizens or immigrants who meet certain requirements. Still, people who are not qualified because of their immigration status can receive Medicaid coverage for emergencies. Also, states can choose to provide additional emergency Medicaid coverage for immigrants who would not otherwise qualify, have low incomes, and are pregnant. However, not all states have done so—which means that many people with pregnancy-related conditions, such as gestational diabetes, are not getting the care that they need.

A recent study supported by NIMHD examined whether expanding emergency Medicaid for prenatal care can help Latina patients with gestational diabetes get the care that they need. The researchers looked at whether access to prenatal care through emergency Medicaid affected health outcomes for Latina patients with gestational diabetes. The study found that expanded prenatal care coverage was associated with significant increases in the use of antidiabetic medications, including insulin, for people with gestational diabetes.

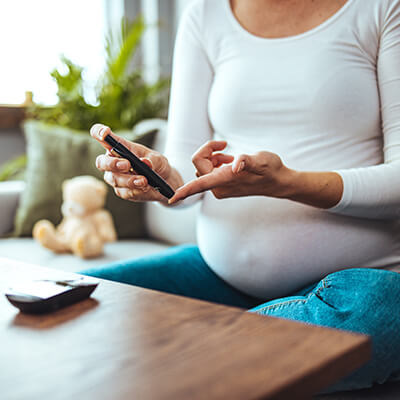

Gestational diabetes is a type of diabetes that can develop during pregnancy in people who do not already have diabetes. It is a common medical condition during pregnancy. Failure to treat gestational diabetes can create severe risks for maternal and fetal health. High-quality prenatal health care can facilitate diagnosis of this condition and help people manage their gestational diabetes through diet, exercise, and, when needed, medication.

In the study, researchers looked at Medicaid claims and linked birth certificates for 1,834 Latina patients who received emergency Medicaid, which means they all had low incomes and were immigrants. The patients all had gestational diabetes and had their babies in a hospital in Oregon between October 1, 2010 and December 31, 2019. Oregon began to offer emergency Medicaid coverage for prenatal care between 2008 and 2013, rolling it out one county at a time. The researchers focused on 21 counties that adopted this policy in October 2013, comparing patients with gestational diabetes before and after that date. As a comparison, the team also gathered data for 1,073 patients with gestational diabetes in South Carolina, which has an immigrant population comparable to Oregon’s and did not cover prenatal care through emergency Medicaid during the study period.

The researchers were interested in whether the policy change in Oregon affected use of antidiabetic medication by pregnant patients with diabetes. They found pregestational and gestational diabetes information from birth certificate data and gathered information about antidiabetic medication through the Medicaid pharmacy claims file. The researchers also looked at additional measures of maternal and newborn health, including gestational hypertension, cesarean birth, and postpartum contraception, to see whether they were linked to prenatal care.

The researchers found that before the Medicaid policy took effect in Oregon, only 0.3% of Latina patients with gestational diabetes used antidiabetic medication during pregnancy. Once the emergency Medicaid policy changed, 28.8% used medication for gestational diabetes. Insulin use also increased. The researchers did not find an association between the availability of prenatal care and gestational hypertension or cesarean birth. However, they did find an increase in postpartum contraception—largely postpartum tubal sterilization—once the emergency Medicaid policy went into effect in Oregon.

The researchers concluded that the availability of emergency Medicaid was linked to a significant increase in the use of antidiabetic medications for those who had gestational diabetes. Gestational diabetes is on the rise and affects the health of both pregnant people and their children—particularly those who do not have health insurance or are underinsured. The researchers point to the importance of expanding prenatal care to people who do not have insurance, have low incomes, and are recent immigrants and who may not otherwise have access to this preventive care. CDC research suggests that most pregnancy-related deaths could be prevented, in part, through quality prenatal care.

The researchers also noted the importance of further investigating postpartum contraception in these populations. About 15% of patients in Oregon underwent postpartum tubal sterilization once there was wider access to prenatal care, twice the national rate for this contraception method. The authors write that this finding could indicate patients’ preference for this method or could mean that they did not have access to more reversible methods of contraception, because they had limited postpartum medical coverage.

Citation

Page updated December 23, 2022